all about Erik

For a while, I was utterly fascinated by the idea of Erik Satie, the eccentric French composer of the once ubiquitous Gymnopédies. In fact, he has figured in my writing twice, and may well again. The piano quintet I wrote for the Flinders Quartet a few years ago was based on an imagined day in his life, but that work was in turn based on an earlier arrangement I made for the Australia Ensemble of his brilliant set of twenty-one pieces for piano known as Sports et Divertissements, which was in turn quite probably based on Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, which was based on… I can’t remember, you probably do. As I wrote almost a chapter of my Masters thesis on these pieces, I thought it might be of interest to post some of that here.

Satie’s pieces have interpolated comments, the oration of which was expressly forbidden by the composer. However, they are so piquant, and so integral to the experience of the pieces — in fact, to virtually any of Satie’s pieces — that I ensured that they were not only included, but featured. For the Australia Ensemble concert, my father-in-law Gerald English provided the declaimed texts, quite brilliantly, as you can hear.

In 1934 Constant Lambert said of Satie that “English critics have been unanimous in their disapproval, and one has yet to see that their contempt is based on any knowledge of his work as a whole. Satie is looked upon (…) as a farceur and an incompetent dilettante.” Bearing this out, fifty-five years later Gerald Abraham obligingly wrote of Satie as “an amusing blagueur of miniscule talent”. It would be hard to argue that Emmanuel Chabrier and Gabriel Fauré were also merely the possessors of such mediocre gifts and yet their music is similarly neglected in the Anglo-Saxon musical world, although perhaps not so regularly maligned. Which just goes to show that Lambert was right when he said: “The theory that music is an international language may be compared to the statement that blood is thicker than water. They are both so obviously untrue that no one worries about them any longer or is likely to protest at their frequent occurrences in public speeches.”

It should not be forgotten, of course, that the criticisms were not limited to the English. Like Ravel, Debussy and the Russian émigré Stravinsky, Satie enjoyed his share of succès de scandale, particularly when his ballet Parade was performed in 1917 to hoots of derision and in the midst of the Dada movement. Whatever reaction his works caused at that time, and whatever one may make of them now, the idea that Satie was a naïve and unskilled artist is demonstrably false. Stravinsky, writing in his autobiography, declared “I liked him at once. He was a quick-witted fellow, shrewd, clever, and mordant. Of his compositions I prefer above all his ‘Socrate’ and certain pages of his ‘Parade’.” Ravel was interested enough to play Satie’s piano pieces on occasion but it was Debussy who was genuinely and significantly influenced by Satie’s unconventional ideas and what Debussy inferred as his musical “medievalism”. Opinions will probably remain divided, however, between those who view the egregiously eccentric and experimental nature of his work as just so much empty self-absorption and those for whom he represents a welcome way out of German Romanticism (and who simply like the music, it must be said).

Three years before the first performance of Parade, one of its precursors and one of Satie’s most exquisitely crafted works was made. The story of how the twenty-one pieces for piano solo that comprise Sports et Divertissements came to be composed in 1914 is fairly well-known, if only for the slightly apocryphal account of the financial arrangements involved. Lucien Vogel, publisher of magazines and occasional one-off art and music books, approached Stravinsky with a commission to write short piano pieces to accompany a collection of drawings by one of Vogel’s house artists, Charles Martin. Stravinsky declined, finding the proposed fee too low. It was one of Vogel’s designers, Valentine Gross, who next suggested that Vogel ask Satie. When the same fee was offered to Satie, he was inexplicably offended and, so the customary version goes, only agreed to the commission if the fee were reduced. In fact, as Volta argues, Satie, who was a rather touchy individual, may have been reacting to the advice of Roland-Manuel, then a friend but later a bitter enemy, to push for too much and so risk losing the commission altogether.

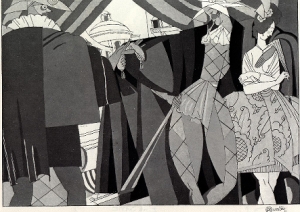

To the twenty drawings by Martin, Satie appended a chorale at the beginning, as he remarked in his own printed introduction. In doing so, was he deliberately making reference to Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire of 1912? Pierrot was arguably a parody of the German melodrama, an 18th- and 19th-century form comprising declamation and music, a typical example of which is Richard Strauss’ Enoch Arden op.38, on an epic poem by Tennyson. Schoenberg’s setting took twenty-one of Giraud’s poems (translated into German) concerning the commedia dell’arte character Pierrot, and famously notated the declamation in Sprechstimme, musically alluding to the cabaret forms so familiar to Satie, as well as a multitude of others. It is no coincidence, then, to find Satie alluding to Scaramouche (“La Comédie Italienne”), Pierrot (“Carnaval”) and the moon (“Le Flirt”, accompanied by a musical quotation from the folk song “Au clair de lune”).

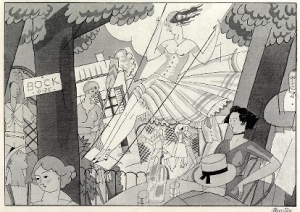

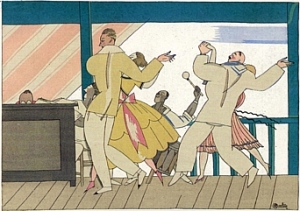

The publication of the book was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I and the liquidation of Vogel’s publishing company. By the end of the war, however, Vogel had reconstituted his company and finally printed the collection in 1923, only two years before Satie’s death and six years after the appearance of Parade. Times had changed, meanwhile, and even if there hadn’t been a Great War Vogel’s fashion magazines would have reflected the one truth concerning their subject: constant change. Consequently, Martin, who had by this time come under the influence of Cubism, had replaced all of his drawings of 1914 and it is these new illustrations that were published alongside Satie’s music and text in three versions of the original deluxe edition: one with all twenty plates by Martin, one with only plates 1—10 and one with only one plate, chosen at random. The Vogel edition has never been republished in its original configuration, so that the full effect of the work as a synthesis of music, text and art can only be imagined. For this purpose, the Dover edition of 1962 is probably the most useful, reproducing the second (1922) set of Martin pictures with Satie’s original calligraphy, which is very distinctive. What is missing, and which can be inferred from Satie’s preface, is colour: apart from the coloured plates, Satie’s score featured black notes and red staves. What is also missing is the opportunity to compare the first and second versions of Martin’s illustrations and examine their correspondences with Satie’s music; in many instances, it is in the first version that the interplay between picture and music is most meaningful.

Both Davis and Volta demonstrate the extent to which Satie involved himself with the popular culture of the day, embedding Sports with references to music-hall and café life, of which he was an enthusiastic participant, and more specifically to the fashionable world of Vogel’s magazines Fémina and La gazette du bon ton. Sports et divertissements itself was in prominent current usage as an advertising catch phrase promoting the modern fad of the moneyed classes to travel to places like Dieppe and the Riviera to take invigorating holidays full of sport and amusements. A comparison between the contents pages of the spring issue of Fémina in 1913 and Satie’s collection is striking. It is a catalogue of contemporary pastimes that is, not surprisingly, caricatured and lampooned by Satie, along with the magazine illustrations’ captions, parodies of which form the basis for Satie’s inimitable “stream-of-consciousness” text inserts. Many of the associations that would have been immediately obvious to musically-minded readers of Vogel’s magazines are not at all obvious today, of course — who is familiar with the monthly Parisian magazines of 1913 and 1922? Some of Satie’s other musical references may not have been quite so easily recognised at the time of publication, though. Davis draws plausible conclusions regarding Satie’s subtle borrowing of material from a range of composers including Bizet, Widor and Debussy and shows that Satie did so knowingly and with considerable technical skill.

This arrangement of Sports was made for the Australia Ensemble, both in the conviction that the instrumentation of the ensemble (flute, clarinet, string quartet and piano) afforded a wealth of colouristic opportunities for creative arrangement, and that the work itself was full of potential for meaningful instrumental colour. Another consideration was the similarity with the instrumentation of Pierrot lunaire (narrator, flute/piccolo, clarinet/bass clarinet, violin/viola, ‘cello and piano), with which it is connected. The existence of fine music that is rarely if ever played and heard in its original form, by virtue of idiosyncratic instrumentation (Grainger’s settings of Kipling’s verse, for example), by the use of obsolete instruments (Schubert’s sonata for arpeggione; Schumann’s pieces for pedal piano) or because the genre is no longer widely practised (piano duet repertoire and, to a lesser extent, organ repertoire), has always been the reason and justification for many arrangements and transcriptions.

Sports was published in a short print run of about 900 copies in 1923. It was known to a small circle of Satie’s friends and acquaintances and to the mainly dilettante clientele of Vogel’s magazines. By its nature, it has never been comfortable in the concert hall; it was almost certainly not envisaged by Satie to be comfortable or, in all likelihood, to be heard there at all. In any case, he is reported on several occasions to have warned against declaiming the words during the performance of any of his pieces, so that the complete experience of Satie’s world is removed one step further away if the the injunction is heeded in public performance. For this arrangement, texts were declaimed, against Satie’s instruction, after considering the alternative. Although declamation and piano mutually interfere in performing the original in this way, the transparency and spread of colours gained by transcription to a small mixed ensemble were found to complement the voice in a way that neither obscured the spoken words nor was obscured by them. To complement the aural performance, in which the original French texts were declaimed, slides comprising Martin’s and other illustrations, photos and translations of the texts were projected with each number.

THE PIECES

When Satie entered the Scola Cantorum in Paris as a mature-age student in 1905, it was in order to remedy a perceived lack of technical grounding that had undermined his confidence for years. Part of his studies involved the traditional discipline of counterpoint, which he found that he greatly enjoyed, especially the emulation of Bach’s chorale settings for four voices. In his introduction he mentions the reason for the inclusion of the extra, unillustrated piece, “Choral inappétissant”, dedicating it to “those who dislike me” and written for the “shrivelled up and stupefied”. In it, he writes, “I have included all I know of boredom”. Yet the piece, without such a caption, is not dissimilar to the Douze petits chorals (1906) or the single chorale-like pieces such as an unnamed one included in the Carnet d’esquisses et de croquis (1899—1913), none of which betrays anything more ironic than a careful and inventive regard for voice-leading. It is characteristic that Satie’s words and music form such a counterpoint, which would have to be viewed as deliberate and suggestive. In performance, of course, such music can acquire irony, both by reference to the text and by exaggeration.

The piece is crammed full of eleven syntactically correct appoggiaturas that might have satisfied d’Indy. The clarinet contributes sparingly and slightly incongruously to accentuate the fourth, eighth and last appoggiatura resolutions, the last emerging as violin II fades.

Davis draws attention to the parallels between Satie’s swing (“La Balançoire”) and the slide (“L’Escarpolette”) by Georges Bizet in his suite for piano duet Jeux d’Enfants (1871). Set for clarinet solo and pizzicato violin II and ‘cello, the only addition in the arrangements is a free vamp at the beginning and end; at either end of the piece the music emerges from, and regresses to, silence.

“La Chasse” and “La Comédie Italienne” are both arranged straightforwardly, using the distinct colour combinations available within the ensemble. The penultimate phrase of “Comédie…” is lengthened and the voicing modified so as to accentuate the comic and dramatic effect of the scale to top F corresponding to the text “Et le reste!”

“Le Réveil de la Mariée” is similarly lengthened by one bar in order for the words “Un chien danse avec sa fiançée” to be absorbed at leisure, while the pianistic figure in “Colin-Maillard” that complements the words “Comme il est pâle” is likewise expanded.

“Le Yachting” is subjected to more extensive arrangement. Repeating the piece allows some of Satie’s figuration to be elaborated in two ways. The original piano accompaniment to the text “Pourvu qu’elle ne se brise pas sur un rocher” is treated imitatively and extended at first hearing in the arranged version and further imitated by a third voice upon repetition.

The unfortunate Colonel whose club splinters as soon as he hits the ball is personified by a clarinet solo in “Le Golf”. Notably, the opening phrase predates the popular song “Tea for Two”. “La Pieuvre” is unaltered from Satie’s original, like “Le Traîneau”, as part of the overall scheme to spread the arrangement across a variety of instrumental solos and sub-groupings.

Like “Le Yachting”, “Les Courses” is repeated, so that two phrases, those corresponding to the texts “Achat du programme” and “Départ… Ceux qui se dérobent”, might be extended and developed, again polyphonically.

Davis remarks that Satie’s quotation of “La Marseillaise” near the end is remarkably similar to Debussy’s own quotation in “Feux d’artifice”, the last of the second book of his Préludes (1913).

Prokofiev’s cat-clarinet visits “Les Quatre Coins”, in which the four mice appear as string pizzicati. Actually, they are all children: “puss-in-the-corner” is a children’s game, and is featured as such in Bizet’s Jeux d’Enfants, whose material is again quoted by Satie (Davis: pp.458—9).

Davis perceives a similarity with the opening of “Le Pique-nique” and the folk tune “Keel Row”, which may or may not be intended, as well as a snippet of cakewalk, which almost certainly is. Debussy’s cakewalk parodies, “Golliwog’s Cakewalk” from the Children’s Corner suite and Le petit Nigar, would doubtless have been well known to Satie, whose own popular song “La Diva de l’Empire” is written in the same style. The brewing storm that threatens to ruin the picnic is doubled in length in the arrangement, for exaggerated dramatic effect.

Satie’s few financially rewarding compositions included the waltzes and waltz-songs “Poudre d’Or”, “Je te veux” and the two early pieces “Valse ballet” and “Fantaisie-valse”. “Le Water-chute” parodies such waltzes, Satie’s stock-in-trade as pianist at the Chat Noir and other cabaret-cafés in Montmartre.

In a similarly light vein, “Le Tango” parodies the dance that was the craze of Paris just before the war. Evidently the charms of the tango were lost on Erik, whose performance direction “Modéré et très ennuyé” signals his evident antipathy, as does his subtitle “endless” (perpétuel), as the trend may have seemed at the time. For anyone wishing to take him at his word (like those misguided enough to take his comments regarding Vexations at their face value…), there is an innocuous repeat sign, with no obvious way of ending. For the purpose of clarity, the arrangement makes the one repeat explicit and makes a coda of the third hearing of the first clarinet phrase.

In “Le Flirt” Davis again discovers musical quotations, this time from a less well-known source, “Le Flirt” from Le Carnaval op.61 by the French organist Charles Marie Widor.

While some of Widor’s fine organ symphonies are known today, his piano music has largely fallen by the wayside. In 1914, though, Le Carnaval may well have enjoyed greater appreciation. Significantly, Widor was the composer of another piano collection, Vieilles chansons et rondes pour les petits enfants, published in 1912 in a lavish production that included colour illustrations by the fashion artist Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel. More than any other, perhaps, Widor’s collection provides the model for Satie and Vogel’s decidedly more sarcastic work for adults.

And finally, “Le Tennis”. Game!

Nice post

Fantastic blog and wonderful arrangements. Thank you!